12 tips to start specialising in cookbook translation

Last Friday, I heard someone trivialising recipe translation on Twitter: what they had to translate was obviously a few easy recipes. As an expert in the making, I will tell you how I got to be a semi-expert in food translation. The trip is not over; I have just embarked on a gastronomy translation course.

I spent the whole summer of 2018 researching, reading and writing about cookbook translation as well as translating 6,000 words of a cookbook for my dissertation, for which I was awarded a distinction. So, how do you become an expert in cookbook translation?

1. Read academic and good press articles about food and cookbook translation

Food translation is fully immersed in culture. Reading about it won’t be hard work, because it is fascinating. To give you an idea, I read about:

- the cosmopolitan cookbook in Victorian times;

- the changing fashions in cookery books;

- the history of cooking programs on Spanish TV;

- the translation of cookbooks in Sweden;

- the taste of otherness;

- Ferrán Adrià’s regional cosmopolitanism,

- the adaptation and retranslation of Jamie Oliver’s Italian series cookbooks and TV programmes for the Italian public;

- the use of Maori food terms as a marketing tool in New Zealand’s guide books;

- masculinity in European cookery shows after the Naked Chef;

- language and gender in female celebrity chef cookbooks;

- the use of food terms by mestizo writers;

- corpora studies for cookbook and menu writers and translators;

- the rocketing business of gluten free products;

- and much more.

2. Study the twenty best sold cookbooks in Amazon in your target country

You will see how translated cookbooks fare in your country and that may give you a hint as to how acquainted your target audience will be with them and what their expectations might be.

3. Read the reviews of various translated cookbooks

I inspected some of Jamie Oliver’s and Ella Woodward’s to see how people found them. I saw the problems they encountered, what they found irritating. It might be about the book rather than about its translation, but it is useful to see how readers feel.

4. Read the reviews of your favourite author’s cookbooks

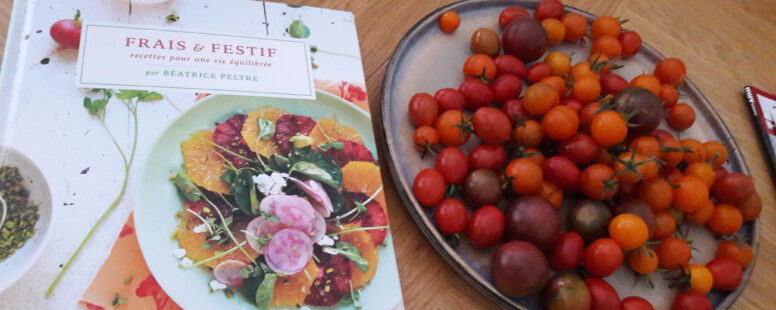

In my case, most of the reviews of Béatrice Peltre’s books (@tartinegourmand) were incredibly positive, but a minority had their complaints. Little spoiler here: first, not everyone likes the hybrid cookbook with its blog-style stories and, second, some people really want to be spoonfed. However, I came to understand these same people making a recipe the other day. Now I feel a little less snooty and better able to sympathise with the differences in culinary prowess in different countries. Will discuss in #ThatTranslatorCanCook.

5. Study traditional cookbooks

And see how they are different from hybrid cookbooks. I inspected Poderosos superfoods and Cocina sin gluten, both by Nuria Penalva (@EdicionesLibsa), both really useful to research vocabulary and to get inspiration for more creative writing. Penalva is quite a good writer.

6. Study hybrid cookbooks

What’s different about their style? Are they addressed to a different type of reader? Hybrid cookbooks are a mixture of literature, blog, travel book (it varies) and recipe repository. I discovered late in my research that the genre had already been imported to Spain. I found and read, Postres Saludables by Auxy Ordóñez (@LibrosCúpula) and Repostería sana para ser feliz by Alma Obregón (@edit_planeta), both with imported elements of the foreign hybrid cookbook, yet with different styles and degrees of foreignization.

7. Study translated cookbooks

And see how other translators did it. Do you like their decisions? Can you see why they made them or do you disagree with them? Do you think they could have done better? Why? I inspected La cocina vegana by Adele McConnell (@grupozeta) and Las delicias de Ella by Ella Woodward (@Salamandra_Ed).

8. Interview a cookbook translator

I was very lucky that the translator of Las delicias de Ella made time to answer some of my questions about his decisions. Whether I made the same or not, they helped me understand and justify mine in some cases.

9. Read modern health magazines

These talk about the latest food trends and include modern recipes made using the latest ingredients. I closely examined @Cuerpomente, a magazine I buy whenever I go home.

10. Watch MasterChef in your languages

I watched various episodes of Spanish MasterChef Junior 5 to see what terminology the public would be familiar with. Do they use lots of word loans? Do they use tons of jargon? Do you think the general public will be familiar with them? Does everyone watch these programmes? How about foreign cookery shows on private channels such as Canal Cocina? Are these available to everyone for them to be familiar with Jamie Oliver and other foreign cook styles?

11. Source useful and reliable glossaries

For example, I found a great baking glossary by CNT-AIT. But, will everyone know this terminology or should you use it with care?

12. Create your own reliable glossaries

I had to research countless gluten free terms, which are rather unstable, that is, different brands and different translators use different terms for the same thing. I also researched the availability of gluten free ingredients in Spanish supermarkets by checking every single ingredient I needed on well-known supermarkets and also alternative shops. But you will find yourself needing substitutions for the simplest ingredients. For example, different varieties of apples and pears are grown and sold in different countries.

So, whoever thought that translating recipes or cookbooks was light work, watch out for the next instalment of #cookbooktranslation describing what it means to translate a hybrid (i.e. mixed genre) cookbook! 🙂

Learn more about food translation

Learn about my services

© Pili Rodríguez Deus | All rights reserved.